There are very few Londoners (and international cricket fans) who are not familiar with the Media Centre at the Lord’s Cricket Ground. Designed by avant-garde Czech architect, Jan Kaplický, this is one of his most renowned ‘spacecraft-like’ architecture projects. Completed in 1999, it received the RIBA Stirling Prize for its futuristic design and has become one of the icons of the sporting world. Kaplický provides us with inspiration here at RISE Design Studio, not only for his futuristic work but also for his interest in his later years in nature and the incorporation of organic shapes in his work.

A new life in London

After beginning his career as an Academic Architect in Prague, Kaplický fled to London in the wake of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. He described a need to escape a country where empowerment was very limited at the time and it was “impossible to achieve anything that was even slightly out of the ordinary”. Not allowed to go to university, buy books, or exhibit his work in public, his move provided him with creative freedom and he soon found himself working on the design for the Centre Pompidou in Paris, under the direction of Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano before they relocated to the French capital.

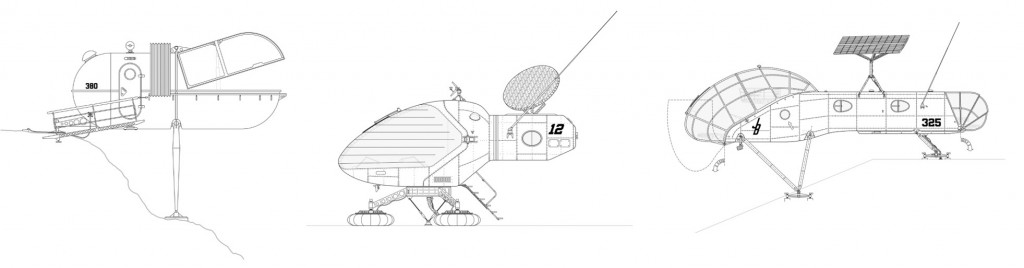

He set up his own architectural practice in London – Future Systems – in 1979, and produced many intricate drawings of orbiting robots and homes transportable by helicopter. Although none of these drawings became real buildings, they drew a lot of attention to his ‘elegantly radical’ ideas, opening the doors for him to design the Lord’s Media Centre and later the Selfridge’s shopping store in Birmingham in 2003. Described as “the ultimate rejoinder to what was then Birmingham’s reputation as a decaying concrete jungle”, Kaplický’s work once again brought inspiration through his visionary designs.

From outlandish to organic

In the mid-1980s, Kaplický suddenly started to look to nature for organic inspiration for his architecture. Perhaps as a result of the death of his mother around that time – she was a well-known illustrator of plants – he had a renewed appreciation of the value of his mother’s work, using shapes of cobwebs, sea shells, mushrooms, flowers and other plants in his later work. Blending these shapes with a harsh and often controversial futuristic edge created a unique style that interrogated the relationship between nature and technology.

The business of buildings

Kaplický’s designs were generally not possible to build using conventional techniques. For example, the Lord’s Media Centre is an aluminum semi-monocoque shell – a sort of ‘boat shape’ – and there was no standard contractor in Britain who could build it at the time. Instead, Kaplický and his life partner, Amanda Levete, found a boatyard contractor in Cornwall to do the work. Combining Levete’s business experience with Kaplický’s designs worked well for several years.

In his later years, Kaplický designed a National Library building for Letná in Prague. Despite the work winning an international competition, its construction was blocked by the Czech authorities and caused much public and political debate. In interviews with Kaplický before his death, it was clear that he was sad not to have been able to build something in his home country.