Architects like most professions welcome industry led guidelines and approaches to inform and improve their work both for their clients, collaborators, and their own progression.

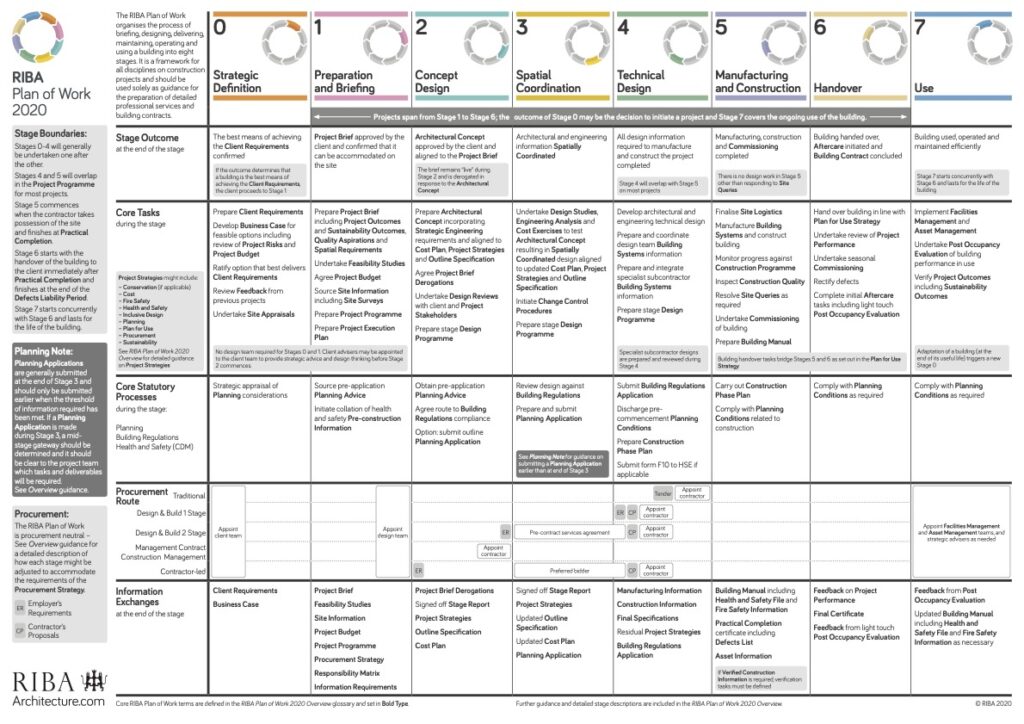

The RIBA Plan of Work 2020 is a guidance document set out by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and is seen as the definitive design and process management tool for the UK construction industry.

First established in 1963 to provide a framework for architects to use on client projects to bring greater clarity to each stage of the process, it has evolved over the years to become an industry wide tool.

To reflect the changing approaches to building design, construction and use, and the associated advances in digital technology, increased ethics awareness, and the prioritisation of sustainable outcomes in line with the RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge, it received its biggest overhaul in 2020.

In this article we examine the eight stages of the RIBA Plan of Work 2020. We look at how this formal roadmap, whilst not a contractual document provides vital guidance and helps to deliver successful outcomes for stakeholders by informing the briefing, design, construction, handover, and use of a building.

Each of the eight key stages has an expected outcome; core tasks; core statutory processes in relation to planning and building processes; and crucial information exchanges, all of which impact the success of the next stage.

Stage Zero – Strategic Definition

‘What do you want to achieve from your building project, and what are your best options?’

This stage is not about design or practical details, but rather a chance for us to get to know the client, developing their requirements and helping shape the business case to achieve them.

At this stage all those involved in the client team, alongside ourselves and any other professional advisors must consider that the proposed building project is the appropriate means to meet the client’s stated objectives, and then determine the best way forward.

For example, perhaps a new building is not the answer, and the solution could be refurbishment or an extension.

To come to a decision, information is gathered for each option. This involves examining previous similar projects, the current building if applicable, analysis of project risk (where appropriate site appraisals and surveys carried out), and consideration of project budgets.

We will look at the size, location, scope, and special considerations around the clients’ needs to further refine the vision.

From this exercise a recommendation is made on the best option, and a business case is completed.

Stage One – Preparation and Briefing

‘Developing the initial project brief and setting out the timescales – the official start of the project’

Once it has been determined that the chosen project and site is the best way forward, stage one, is the process of preparing a comprehensive project brief and choosing the collaborative project team, allocating specific roles and responsibilities.

The project team will include:

– Design team – headed up by Lead Designer and overseeing the design programme

– Client team – headed up by Project Manager and overseeing the project programme

– Construction team – headed up by Project Director and overseeing the construction programme

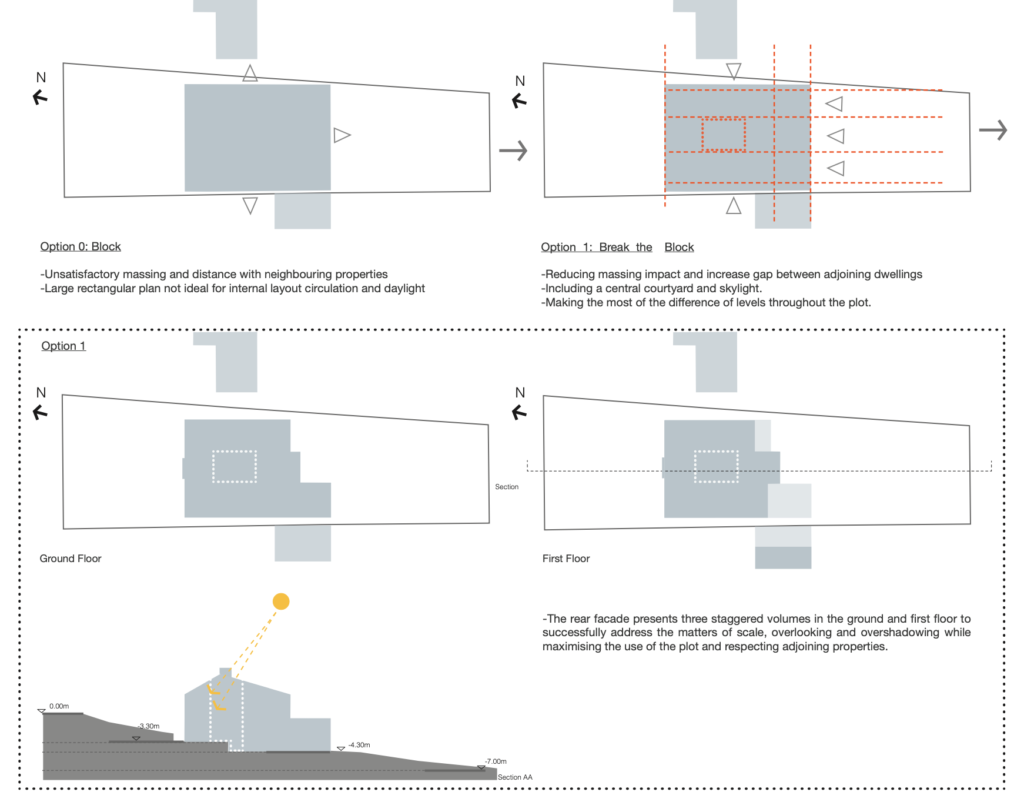

Feasibility studies and site surveys may be required at this stage to test the brief against the chosen site and budget i.e. are there any access issues? Is it a sloping site? What is the spatial overview and relationships with neighbouring buildings?

This is often the time for us to discuss options regarding the site with the local planning authority and make sure there are no constraints. We like to establish clear and positive communication with these departments from the outset.

Discussions around building regulations and other legal requirements should happen at this stage including whether the site is within a listed buildings or conservation area

It is at this point that objectives are finalised and recorded under:

– Project Outcomes

– Sustainability Outcomes

– Quality Aspirations

– Spatial Requirements

Working with the client, we will at the end of this stage, produce a timescale for the project as well as a project execution plan setting out delivery.

Stage Two – Concept Design

‘The design stages begin and the architectural concept is defined ‘

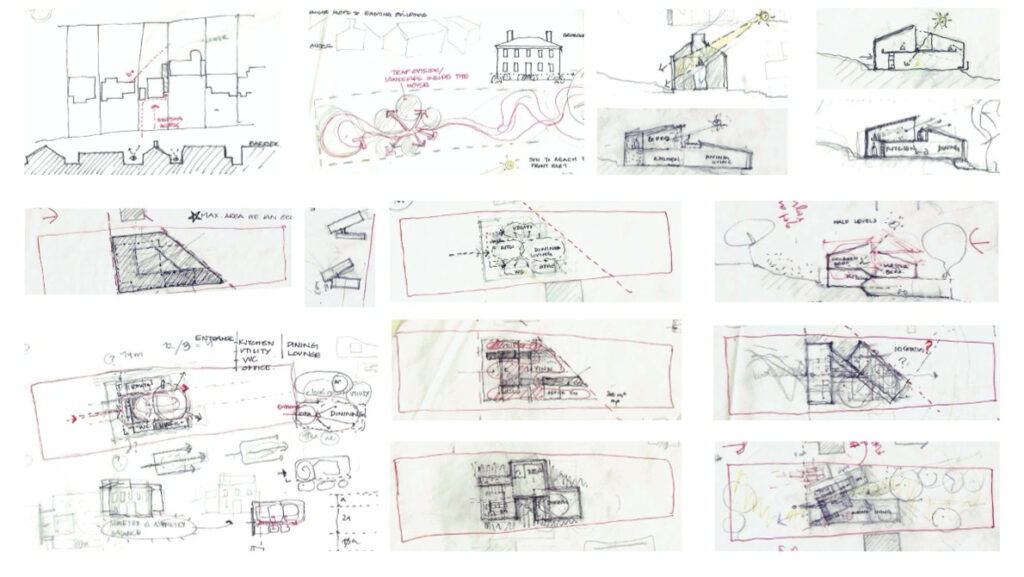

Stage two begins the core design process which culminates at stage four.

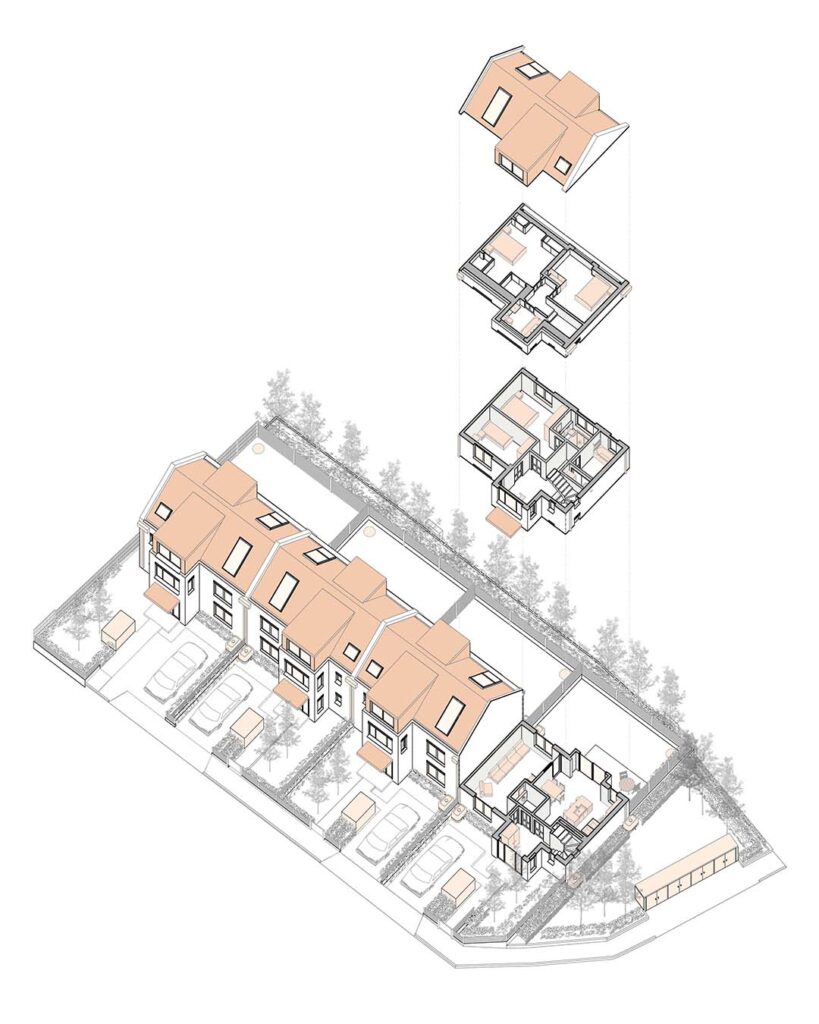

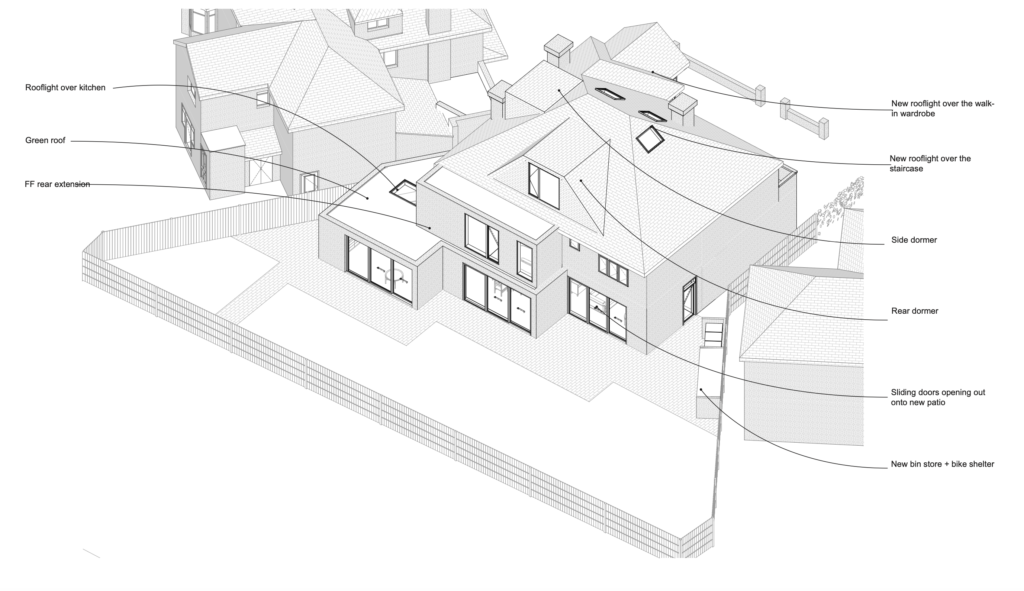

We work closely at this stage with the client to produce visualisations, 3D models, and drawings of the architectural concept, ensuring it meets their needs and is aligned to the project brief and cost plan.

As well as a visual representation of the building with sections and elevations and how it sits within the surrounding environment, these will often include:

– Interior and exterior renders

– Landscaping

– Specific requests

– Strategic engineering requirements

There is as the RIBA states ‘no right or wrong approach’ at this point, it is our initial design response to the brief and will involve regular meetings, discussions and reviews with the client and specialist stakeholders including planners and those across structural and civil engineering, to shape and define it.

The robust architectural concept along with the project brief and cost plan are signed off at the end of this stage.

Stage Three – Spatial Co-ordination

‘The co-ordinated design takes form.’

Formerly the developed design stage, here our team draw up the client approved design in CAD or ever increasingly with BIM, and develop and test it alongside detailed structural design, outline specifications, building services and cost analysis to ensure its viability.

Our design will incorporate the practical elements relating to:

– Window, door, stairway, and fire exit locations

– Fixtures, fittings

– Proposed materials

– Load bearing mechanical information

– Mechanical, plumbing, and electrical considerations

– Tech and security

– Green, eco and solar

During this stage, or certainly at the end the design is finalised into a single model, not prone to change, and planning applications are ready for submission incorporating all our detailed drawings and reports.

Stage Four – Technical Design

‘Final design stage before construction begins’

We make further refinements of the existing design at this stage, incorporating where relevant detail from specialist sub-contractors such as lighting specialists, kitchen designers or glazing companies.

From this our Lead Architect prepares comprehensive drawings, specifications, and documents for tender.

The level of detail will depend on the size and scope of the project but by the end of this stage all elements will be prescriptive rather than descriptive for the project to be manufactured and built, i.e., they set out detailed descriptions around the following:

– Requirements relating to regulations and standards

– The specific types of products and materials required

– The methods of delivery and installation

– The building systems in place i.e., flooring, partitions, mechanical and structural

At the end of this stage all information required to construct the project is completed and we send out the tender to 3-4 contractors we have worked with before. Of course, should the client want to add to the list we will do so.

Stage Five – Manufacturing and Construction

‘All systems go…construction begins’

The design process is now complete and the appointed contractor takes possession of the site to carry out works as per the schedule of works and building contract. This includes manufacturing off-site and construction on-site.

Stage four and stage five can overlap or run concurrently dependent on the size and scope of the project, or when the contractor was appointed.

The client can choose to appoint us as the contract administrator at this point should they wish. In this role we act as the middle ground between the client and the contractor to ensure that all works are being done in accordance with finalised drawings and specifications. This can entail:

– Chairing construction progress meetings

– Preparing and issuing construction progress reports

– Co-ordinating site inspections

– Dealing with site queries

– Agree reporting procedures for defects

– Issuing project documentation to the client

– Issuing certificates of completion

If appointed, we like to meet weekly with the client and the relevant parties to ensure that everything is running smoothly.

The appointment of Building control by the client should take place, to oversee the project and ensure that all is in order in relation to the necessary construction standards.

Health and Safety inspectors will review and observe the site at this stage, so it is worth considering an independent consultant to ensure that all the correct procedures are followed.

Stage Six – Handover

‘The completed building is finished and handed over’

After practical completion, the building is ready for hand over to the client, and the building contract concludes.

Feedback and building aftercare exercises take place during this stage to act as future learnings for ourselves, the client, contractor, and consultants, and to address any issues relating to the integrity of the building.

These involve light touch post occupancy evaluation and snagging processes, whereby the client compiles a list of defects or incomplete works, overseen by us as the contracts administrator and presented to the contractor to rectify.

They then have an agreed Defect Liability Period, usually six to twelve months to address these, after which if all has been made good, building control will sign off the construction and we will sign off the project as a whole.

We then issue a final certificate, and this stage is complete.

Stage Seven – Use

‘The vision for the building is realised and it is now in use’

This stage starts concurrently with stage six.

The building is now occupied and in use. On most projects, our design team will have no duties to fulfil here.

However, the incorporation of this stage into the RIBA Plan of Work 2020 gives the client the opportunity to get in touch with us if they require general advice relating to maintenance, energy consumption or management of the facilities.

We welcome this communication as we love to hear how the client is finding their new building, and it also allows for effective aftercare, valuable feedback, and building monitoring especially around energy consumption, and is therefore key to the sustainability strategy.

The addition of this feedback stage has made the Plan of Work cyclical as it unites the entire process into one, allowing for proper use of the building and then when demands change, and the building reaches an end of life where refurbishment or a new building may be needed, stage zero starts again.

Embarking on a design and build project can often be a complex one for all involved, for a client it can be daunting.

The RIBA Plan of Work 2020 offers all stakeholders a clear approach to map out the journey collaboratively from vision, through to design, construction and eventual use.

At RISE Design Studios, we find that this straightforward process with realistic and measurable targets, the ability to review progress and a provision for valuable learnings allows for enhanced clarity, greater realisation of vision, and successful outcomes no matter the diversity of projects.

For more information on the RIBA Plan of Work 2020 visit RIBA Plan of Work (architecture.com)

If you would like to talk through your project with the team, please do get in touch at mail@risedesignstudio.co.uk or give us a call on 020 3290 1003

RISE Design Studio Architects company reg no: 08129708 VAT no: GB158316403 © RISE Design Studio. Trading since 2011.